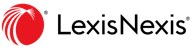

A T-shirt boldly printed with the word "INNOCENT" was held high to a rousing round of applause by O'Neil Blackett, Innocence Canada's most recently exonerated client, at the start of the Fifth International Wrongful Conviction Day reception.

Blackett, who was wrongfully convicted of killing a 13-month-old girl that was in his care, was exonerated on Oct. 2 after serving over four years in jail. His story has been added to the list of 22 exonerees that Innocence Canada, a non-profit organization, has fought for over its 25-year history.

The reception, held Oct. 3 at the Law Society of Ontario, drew attention to the plight of the wrongfully convicted as well as the efforts of the legal professionals who advocate on their behalf. Stories were shared, awards given and promises were made to never give up on fighting for the innocent.

"I know, and am sure, that the weight of that [wrongful conviction] burden is incalculable both for you and your families," said Marlys Edwardh, a renowned civil rights lawyer and one of the first women to practise criminal law in Canada.

Edwardh was given the Rubin Hurricane Carter Champion of Justice Award at the reception for her work in defending the wrongfully convicted. The award highlighted her representation of Donald Marshall Jr., Guy Paul Morin and Steven Truscott.

In her acceptance speech, Edwardh said that the administration of criminal justice has "bitterly failed" each of the wrongfully convicted in attendance. She noted that when she turned to the practice of law in 1976 after completing a "law school education" the picture painted in her mind was that the "criminal justice system was finely tuned."

"In fact, we were told, that the system was so finely tuned that the structure ensured that it was better to let 10 guilty men go free than convict one innocent. Many people believed we'd gone too far, created rules and procedures that coddled the criminally accused. We were not taught, as criminal defence lawyers, to step back, take stock and assess what work we had to do," she explained.

Edwardh took this moment to draw attention to her award's namesake, a professional boxer who spent almost 20 years in prison for a murder he didn't commit.

"He never received an apology from the government. He never received a cent of compensation," she said, adding that Carter's efforts as an exoneree advocate helped in establishing Innocence Canada.

Upon receiving the award in Carter's name, Edwardh thanked the room and said this "means more to me than you'll ever know."

Two other awards were handed out that night, the Tracey Tyler Award and the first Donald Marshall Jr. Wrongly Convicted Award.

The Tracey Tyler Award is named for the Toronto Star's former legal affairs reporter who spent most of her career helping shed light on the stories of the wrongfully convicted. The 2018 recipient was Tim Bousquet, of the Halifax Examiner, who was honoured for his investigative journalism.

Bousquet started a series called "Dead Wrong", which examined the murders of women and girls in the Halifax area. While accepting his award, Bousquet drew attention to Glen Assoun, a man who has maintained his innocence while being convicted of killing his former girlfriend, Brenda Way.

Although Assoun was released in 2014, Bousquet said he has not been exonerated.

"He's living in a legal limbo and for him it's a living hell," he explained, adding that this has led to mental health issues for Assoun.

"It's up to us to work on his file," Bousquet said, while thanking Innocence Canada for the award.

The Donald Marshall Jr. Wrongly Convicted Award was awarded posthumously to its namesake, who was wrongly convicted of murder when he was 17 years old. Marshall ended up spending 11 years in prison before he was exonerated in 1983.

Innocence Canada highlighted Marshall's case as the first to be recognized as a wrongful conviction in Canada, which led to the first inquiry into the cause of a wrongful conviction. The organization created the award to honour individuals who, despite devastating consequences, did not give up on the fight to clear their name.

Marshall died in August 2009. The award was accepted on his behalf by his brother, Terrance, his nephew, Paul and his former partner, Jane McMillan.

Edwardh said, "Junior was a man who symbolized the struggle for justice." She noted that the commissioners who led the inquiry into the wrongful conviction received Marshall's "full participation," which led to a list of important recommendations.

"A remarkable thing that they said was that the administration of criminal justice in Nova Scotia had failed Donald Marshall Jr. at every turn. They went on to say, in part, that failure was because he was a native man. Junior's shoulders were broad. He understood what the struggle for justice was for. He never wavered and never stepped back. And this is why today some of the important changes in the administration of justice have taken place," she explained.

Edwardh noted that in June an Indigenous court was established on a reserve in Nova Scotia, which was one of the recommendations made in the Marshall Inquiry.

"Remarkably the Nova Scotia government decided that they were going to do it with the encouragement of the Mi'kmaq community and some very, very thoughtful judges," she added, stressing that the First Nations need more support from the justice system.

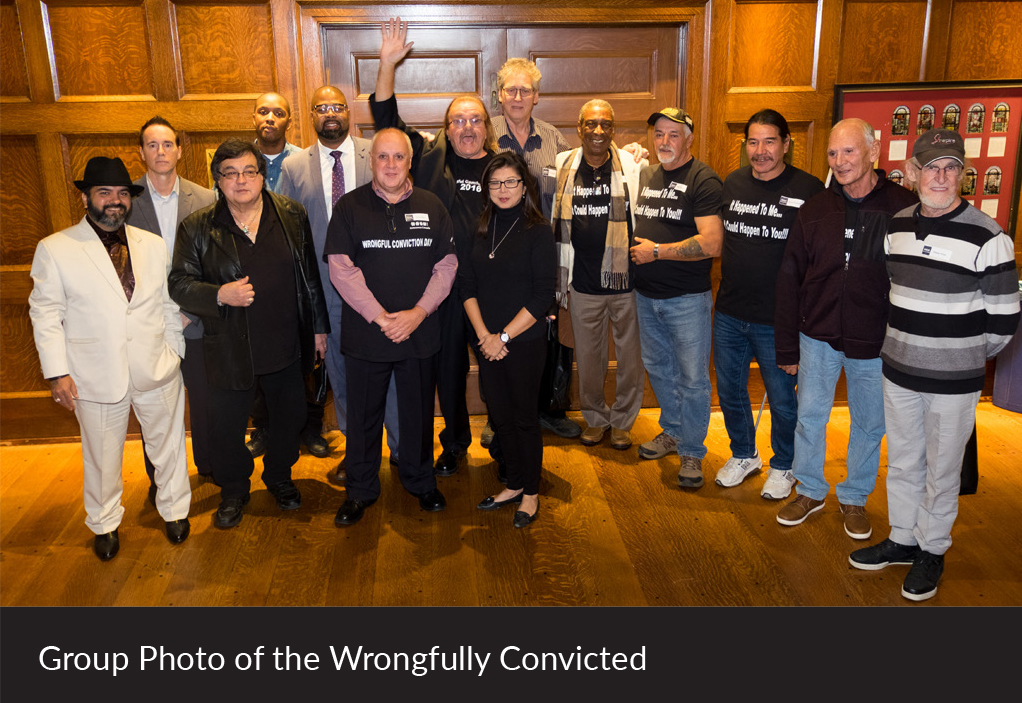

Innocence Canada co-founder, James Lockyer, made one of the closing remarks and said he tried to find a single word to describe the organization's exonerees. Words such as calm, fight, dedication, determination, grit, trust, dignity and joy filled his mind as he remarked on the spirit of the wrongfully convicted.

"Where do we go from here?" he asked the room. "We've had 25 years, good years, but we need to catch up the numbers with the years," he added, noting that 22 exonerees in 25 years is not enough.

"We still need to recognize that our appeal courts across the country aren't doing their job because most of the people we have in front of us, they lost their appeals," said Lockyer, stressing that the courts need to catch these cases.

"They should be more prepared to look at cases and determine whether or not the individual whose case they're hearing is likely innocent. Not looking just at process, but questions of innocence as well," he explained.

Lockyer emphasized that everyone in attendance believes in justice "no matter how difficult it might sometimes be to find."

"Twenty-five years ago, we started this. When you start something you never really think that it's going to last 25 years. But it makes you wonder if we'll perhaps be here 25 years from now in 2043, and there's every reason why we should because people will still be wrongly convicted between now and then," he said.

Lockyer asked everyone in the room to say to themselves, " 'if I'm still around 25 years from now, I'll still be here fighting this cause.' Because then we'll know that we will still be here in 25 years making a small, but a very important contribution to the cause of justice in Canada."

This article was originally published in Law360™ Canada . Event photos by Fardeen Firoze. LexisNexis Canada is a supporter of Innocence Canada.